WhoTracks.Me

The Trackers Who Steal

The Trackers Who Steal

We're all aware of the trackers siphoning off information about you as you browse the web. These trackers are mostly doing this for some business intelligence related reason - websites use these services to try to 'better understand' their customers, or to target them in order to attract their attention in a way which will benefit that website owner - be-it increasing the value of products customers put into their shopping cart, or increasing the likelihood that they click an ad.

However, there is another kind of tracker which is more nefarious than these. These are hidden scripts placed by hackers on E-commerce sites which try to steal your credit-card details as you enter them. In the last year a string of attacks — dubbed 'Magecart' — have affected major sites, including British Airways, Ticketmaster, NewEgg and VisionDirect; stealing payment information from millions of consumers.

At WhoTracks.Me we are monitoring the third-parties loaded on millions of pages per day, therefore once we know the domains that these hackers are using to send their stolen data, we can analyse the extent and impact of these operations. In this article we provide a post-analysis of the four big breaches this year, plus some insights our data gives in on-going attacks.

Four high-profile breaches

British Airways

In September 2018, British Airways announced that a security breach had led to a large theft of customer data. RiskIQ's write up of the breach explains how the attackers compromised a script on the payment page, such that it would send credit card information to a domain owned by the hackers: baways.com.

With this information we can query our data to look for page loads where baways.com was a third-party. This allows us to verify the extent of the breach, and how many users were affected. Our data shows that:

- www.britishairways.com was affected between August 22nd and September 5th. 193 pages in our data were affected1.

- We also see two page-loads on hotline.ba.com on the 30th August where data was sent to the attackers.

This data corroborates the statement by BA on the breach, that users entering card details "between 22:58 BST August 21 2018 until 21:45 BST September 5 2018" would have been affected.

Ticketmaster

In June 2018, Ticketmaster declared a hack of customer information. Again, RiskIQ's analysis tells us how it happened - this time involving a breach of the third-party supplier Inbenta. Compromised Inbenta scripts were then loaded on ticketmaster payment pages, and these scripts then skimmed credit card data input by customers and sent it to webfotce.me.

Unlike the British Airways case, this was not a targeted attack on Ticketmaster, rather a generic hacking program which affected many other sites. We can access the extent of these hacks by looking for the webfotce.me domain in our data:

- Ticketmaster's UK, Irish and New Zealand sites were first affected on February 10th. The malicious script remained in place until the June 23rd, and we saw over 2,500 page loads making requests to the hackers during this time.

- Their German and Australian sites appear to have been affected earlier, with our first observations on December 10th 2017 for ticketmaster.de and December 20th for ticketmaster.com.au. These sites were fixed at the same time as the others.

In their disclosure, Ticketmaster say that UK customers were affected between February and June 23rd, and international customers could have been affected from September 2017. Again this matches up with our data, though we have no observations for international sites before December 2017.

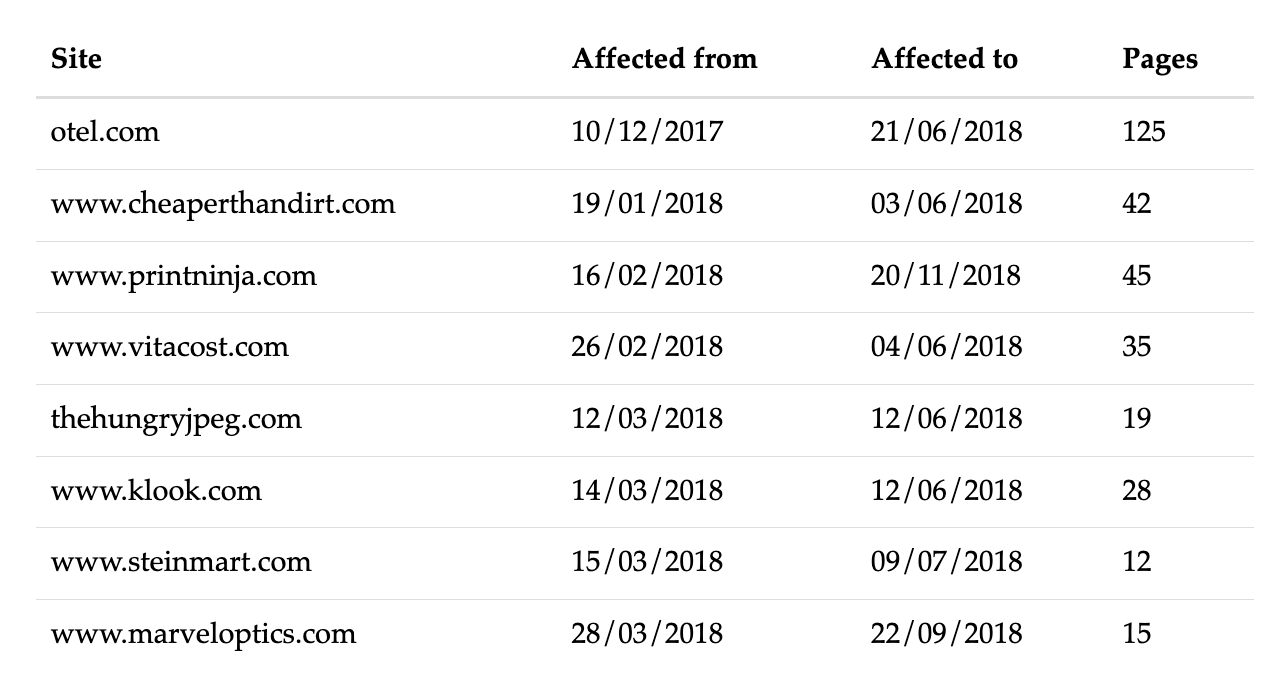

Our data also shows several other sites affected by this attack:

Compared to Ticketmaster, the impact of the breach on these sites is much smaller. Correlations between the dates of infection indicate that these sites were probably infected via a shared third-party (i.e. Inbenta) which was compromised. This shows how hackers can quickly achieve much greater scale by going for third-party services whose scripts will be loaded on many different sites.

NewEgg

Like British Airways, NewEgg were hit by a targetted attack. In this case the collection server was specific for the target. The hackers registered neweggstats.com in order to have a legitimate looking domain so that they could avoid suspicion for as long as possible.

Looking at our data, we see that pages on secure.newegg.com were sending requests to neweggstats.com for just over a month, between 15th August and 18th September, with 90 pages affected in our dataset.

By "Pages Affected" we mean the number of page loads where we saw some third-party call to a server associated with MageCart operations.

VisionDirect

On the November 19th, VisionDirect, a large UK-based glasses retailer, announced that their sites had been compromised between the November 3rd and 8th. In this case, a script was injected into the page from g-analytics.com which pretending to be a Google Analytics script. The difference is, that it will also send credit-card numbers back when it sees them in the page.

Our analysis shows that VisionDirect's European sites (.fr, .it, .es, .co.uk, .eu and .nl) were all affected from the November 3rd. On the .nl and .ie sites we still observed pages contacting the attacker's server on the 9th of November, suggesting that the malicious code may not have been completely removed as early as the press release suggests.

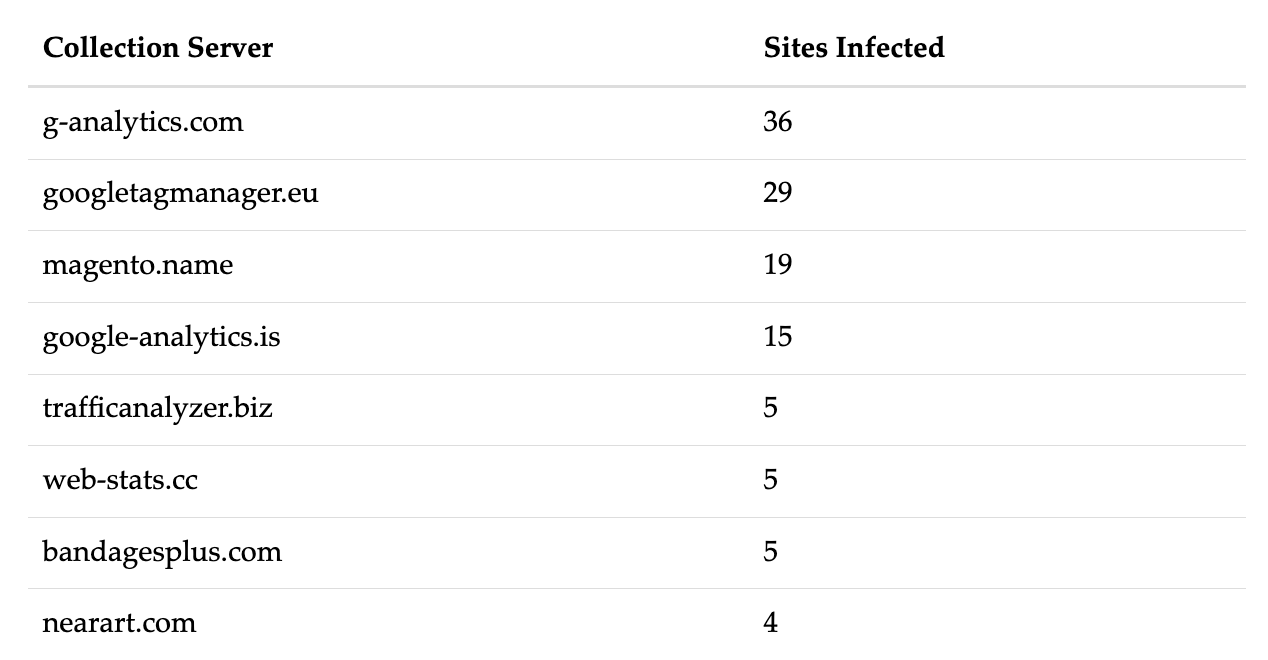

Compared to the other collection servers, g-analytics.com is currently much more active with 36 sites infected during November. We have, however, observed a shift in traffic since November 20th, with almost all sites which were previously infected with g-analytics.com switching to loading a script from google-analytics.is instead. This indicates that the attacks have ongoing access to these sites, allowing them to update their attack code.

Breach detection

While WhoTracks.Me was originally conceived as a transparency tool to show trackers directly or indirectly placed by site owners, this investigation as opened up another angle on this data. We can now effectively track the spread of malicious code being used to defraud web consumers. This capability can be taken to multiple different directions:

- Once the collection servers (or drop servers) are known, we can quickly find and notify websites that are compromised. This can reduce the exposure time of websites, and thus reduce the risk to the average web user. (Thanks to the work RiskIQ have done here to collate a list of active drop servers).

- We can audit breaches that have occurred, and make sure websites properly notify their users. The GDPR requires that companies notify users and authorities when user data is compromised. This data can be used to hold companies accountable if they try to dodge these responsibilities.

- Given the set of collection servers we already know, we can develop algorithms to automatically detect third-parties in pages which are similar. This would then allow us to detect and block these servers even earlier.

We are very exited to start exploring this direction for our data.

Third-party scripts: A security liability

In all of these hacking cases, the entry point has been a malicious script which is loaded in the main document of the page. When this happens on a payment page, the attacker can read all of the information entered: credit card number, CVV, etc. Therefore, any script loaded on a payment page is potentially a critical security weakness.

With this in mind, we should be critical of the current careless way that scripts of scattered onto what should be secure webpages. In the case of the four big breaches we have outlined here, now standard browser security features could have prevented or limited the amount of data stolen:

- Subresource Integrity on script tags would prevent surreptitious changes to first- and third- party scripts (provided the site's own webserver is not also compromised). If a script were to be changed to add the attacker's code the browser will refuse to load it. In the British Airways case one JavaScript file was edited to add the attack payload; for Ticketmaster the attack payload came via a third-party script. This technique provides some protection when loading content for less-trusted origins in pages which require high security.

- The Content Security Policy (CSP) header can be used to prevent requests to unknown origins. In all of these cases the credit card information was sent to a third-party collection server. A CSP header would have prevented this request, thus preventing the malicious script from exfiltrating data.

As well as these high-profile cases, many of the other sites affected by these attacks are smaller E-Commerce sites using off-the-shelf software to run their business. It is therefore difficult for these sites to deploy these more advanced protection methods - even more so because the loading of 20 or 30 different untrusted third-parties on a webpage has become normalized, so users or even developers would not be able to detect unexpected third-parties appearing on a page.

Related to this is another tactic employed by these hacking groups: registering domains very similar to common third-party trackers so that developers do not notice that the site is compromised. Some examples:

- g-analytics.com, pretending to be Google Analytics;

- googletagmanager.eu -> Google Tag Manager;

- slripe.com -> Stripe;

- typeklt.com -> Adobe Typekit;

- crtteo.com -> Criteo;

- jsdellvr.com -> JSDelivr

Protecting users

As we can assume that sites will continue to get hacked, we require a way we can protect users from having their data stolen without relying on site owners. This is where the browser comes in - as the user-agent it should be able to protect the user from attacks like this, much like it already does with phishing and malware sites.

Luckily, as all of these attacks rely on collection servers to receive the stolen data, once we know of a server address we can use block lists to prevent the browser from contacting these servers. Therefore, even when sites are compromised with malicious Javascript, this code will not be able to contact the hacker's server. For Cliqz and Ghostery users we have already distributed a block-list to block these domains and protect them from credit-card theft.

Blocking is just a reactive measure though. Domains are cheap, and sites are getting hacked all the time, so these hackers could easily turn over their domains faster to mitigate our blocking. Therefore, a more robust solution has to incorporate fast detection of these drop servers in order to minimize the effective lifetime of each attack. We hope to incorporate the WhoTracks.Me data in the hunt for these domains, and to emulate the speed that we are already able to detect phishing sites.

Conclusion

In this post we've shown a new angle on the data we publish on WhoTracks.Me. As well as providing transparency on which companies are tracking you online, we are also able to turn this transparency on web criminals who are stealing from web users. This transparency can be used to:

- ensure that breaches are reported promptly when they occur;

- assess the impact of breaches, in terms of the time span when sites were affected and how many users may have been affected; and

- develop new techniques to catch these operations faster and reduce the number of users who suffer from them.